Emu

Life on land

Your support will assist us to continue our research and content development, the greater our resources, the more we can do.

The more we have an accurate understanding of what is happening to nature, the more we can all do to protect what remains of our living planet.

This is also an opportunity for philanthropists to be part of an ongoing project that tells independent stories about the natural world, stories that will help us to better understand what is happening to species and places on our precious planet Earth.

Note: Creative Cowboy Films does NOT have tax deductible charity status.

The Nature Knowledge Channel is a very real way you can help the precious natural world and support the work we do in creating knowledge about the natural world.

Annual membership of the Creative cowboy films - Nature Knowledge Channel gives you full access to content, stories and films, available on this website. Becoming a member of the Creative cowboy films - Nature Knowledge Channel is a very real way you can help the natural world and support our work in creating a greater understanding about what is happening to it.

A point of difference

Creative cowboy films is independent, is not funded by governments or industry, and is not influenced by their associated interest groups. For reasons of independent research and content development, Creative cowboy films does NOT have tax deductible charity status.

Life on land

The story today about what is happening to Emus is yet another and immensely sad one that reflects the present and disgraceful conduct towards the native plants and animals of Australia. We begin in the beginning.

We stand in a wild place and there in front of us and still distant is a family group of about twenty Emus Dromaius novaehollandiae. We stand quite still with our cameras in hand. Instead of rushing away, one bird spots us, both curious and cautious, the whole group come over to where Andrea and I are standing in a flowing and undulating whole. to inspect us.

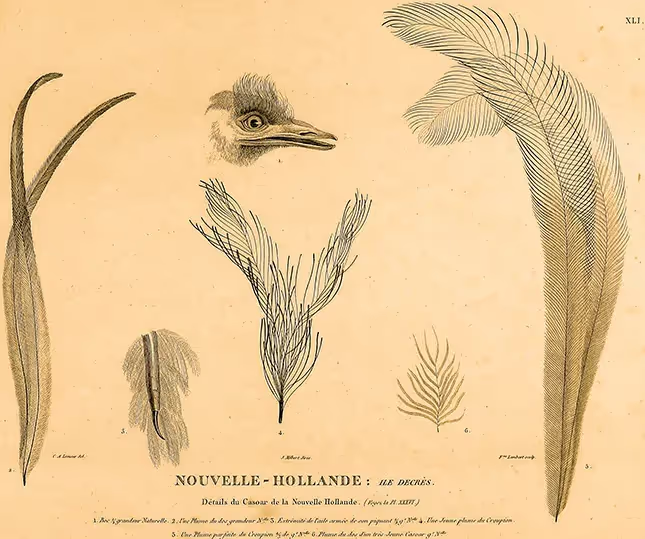

What a beautiful thing. The overwhelming impression is of softness, gentle animals, softened further still by their extraordinary double shafted harp like feathers rippling in the wind. The tallest of these flightless birds are precisely the same height as me. And that is six foot two.

In the film above a very special Emu, who has become our friend, shows off his agility and speed. We love to visit our Emu friend who gets very excited to see us. The Emu, entirely wild, comes for walks with us. We have also sheltered our Emu from shooters as we all tried to get away from the slaughter of Kangaroos unfolding before us.

The Emu was terrified and so were we.

Part of that excitement of being with us is to demonstrate a remarkable ability, and that is to run very very fast. Thrown into the display, the occasional acrobatics, a skip here, a twist there. Incredible to watch and what a joy.

It is not surprising that Murray Garde’s (editor) recent book Something about Emus: Bininj stories from Western Arnhem Land (Aboriginal Studies Press 2016) begins where we began in our search for the bark paintings of Arnhem Land, now long ago, with Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek, Jimmy Kalarriya and Mick Kubarkku. All men so dear to us, and in their lifetimes, Emus were there in ceremonies and dreaming stories. Jimmy, a member of the Wurrbbarnbulu or Emu clan whose estate was located deep in the rock country of the Arnhem Land Plateau.

The relationship between Aboriginal people and Emus is both long time and complex. The art of the artists of the region, where Emus feature in the works, is compellingly beautiful. The men knew that there were many things to be learnt from Emus. Jimmy’s Emu paintings collected from Manmoyi out station where they had been created many years ago.

Lofty describes how the male Emu incubates the eggs in a discussion with Mary Kolkkiwarra at Kabulwarnamyo outstation.

“He lies down like this, the eggs are in the middle and his knees lie down but all the eggs are laying there. The lower (parts) of the legs are on either side of the eggs. He puts his body on top of the eggs to cover the eggs over. The Black-breasted Buzzard can’t see them, but sometimes it can smell them”.

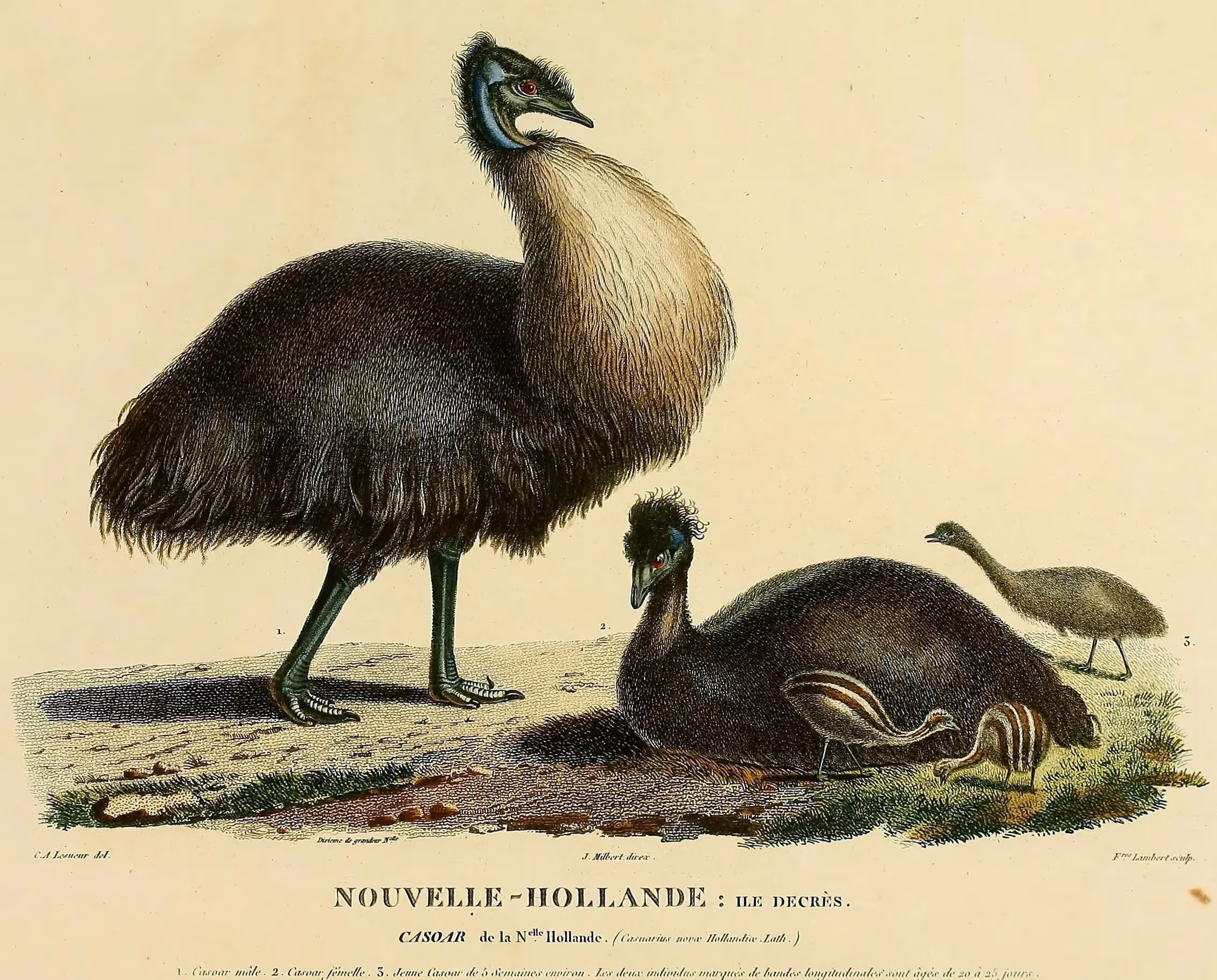

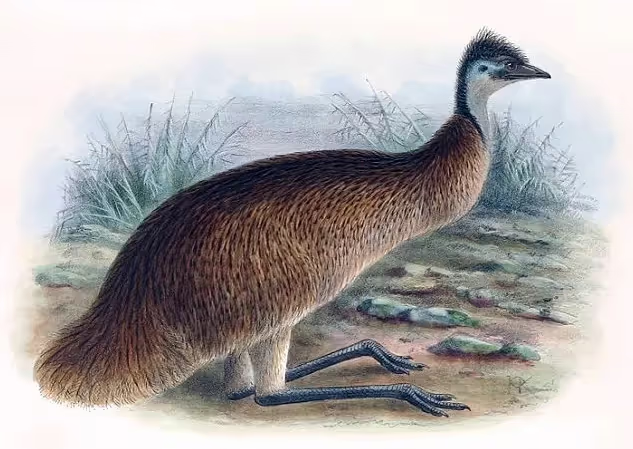

In the Late Quaternary period the Emu had several and smaller relatives living on various islands off the coast of mainland Australia. These included Emus on Kangaroo Island (Dromaius baudinianus), King Island (Dromaius ater) and Tasmania (Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis), all of which are now extinct following European settlement. The smallest was the King Island Emu. The Tasmanian subspecies of the remaining mainland Emu species became extinct in the mid 1860s.

Other species are know from the fossil record. In 2018 two bones from a new species of Emu were discovered in the important fossil beds at Alcoota in Central Australia, a place we first visited in the 1980s. Over decades small fragments of bones have been discovered suggesting this was an Emu. We now know that the newly discovered species was also a dwarf Emu and around the same size as the King Island species.

The first Emu 'specimen collected' by Europeans was from what is now Redfern, an inner suburb of Sydney, in 1788.

Emus are caught up in the slaughter that is occurring to various species of Kangaroo, a common trick is to run them down on fence lines, to shoot them indiscriminately along with the Kangaroos and to commit acts of gross cruelty in other ways. Much of this behaviour ensures the agonising death of these harmless and often charming large birds. The pretence, as for Kangaroos is that Emus are plentiful, even growing in number for the same reasons that Kangaroo populations are meant to explode. Rubbish of course, but the myths continue.

Here is an example of a recent scandal, caught on film, of one individual’s actions (he apparently thought it was fun).

“Video footage of Jacob McDonald knocking down the native birds like bowling pins while laughing went around the globe, sparking public outrage and a nationwide manhunt”.

Unlucky for Jacob that he made his crimes so obvious by recording and posting them on social media, this means that the usual excuses for these kinds of acts of cruelty (usually involving girlfriends or grandmothers) are unlikely to mean much and it makes it hard for governments to turn the usual blind eye when it comes to the horrific cruelty directed at Australian native species. What Jacob did however occurs over and over again and almost nothing happens to stop it.

In the period 2009 to 2017 the Victorian Government alone, and Emus have largely been exterminated from Victorian landscapes, issued kill notices (ATCWs) for 8,740 of these beautiful and very big birds. To date (end 2021), and since 2009, the Victorian Government has issued permits to kill 12,122 Emus. That is an average of 933 each year.

We may well ask ourselves why?

Numbers being killed under Victorian Government permits appear to be in decline and the reason for this will be the continuing decline and distribution of the Emu population in the State.

They will not stop until they are all gone.

The French explorer Nicolas Baudin arrived at King Island in Australia’s Bass Strait in 1802. Baudin’s expedition was the first to document the dwarf King Island Emu, which was roughly, at one metre, just half the height of its mainland cousin. King Island already had European visitors, but small in number.

These were the sealers who had come to slaughter the vast Elephant Seal colony that existed on the island at that time. In one sense the King Island Emu was collateral damage to this slaughter. In the diminutive Emu, the sealers had an easy target and easy food source all around them.

Baudin did capture a number of King Island Emus, intending to take the birds back to France, most died on the journey despite the elaborate attempts to get them back safely, but in 1806 two birds, a male and a female did make it to Paris. When Baudin arrived on the island there were just thirteen European inhabitants, more came and by 1810 all of the Emu’s habitat had been destroyed and the birds were extinct with the exception of the two birds now living in Paris. These last two birds died in 1822, so that was the end of yet another Australian species.

Extensive damage has recently occurred to the coastal dunes where the extensive fossil record and bone beds of the King Island Dwarf Emu were located because a golf course was built on the site and the dunes were flattened by heavy machinery during construction.

Our concern for the Emu is this, while the species is not hated (nor is its hatred obviously promoted by industry or governments as is the case for Kangaroos) no one appears to particularly care about the big bird. These beautiful and inquisitive animals deserve a great deal better.

I will leave you with Gerald Durrell’s encounter with an Emu during a visit to Australia in 1962.

“He had now twisted his head almost upside down, presumably to see if my face looked more attractive this way up. He gave another burst of drumming and then, digging his feet into the ground, pushed me inexorably towards the nest. I felt the implication was that I should share with him his labour of love, but I had better things to do than squat on Emu eggs. Slowly so as not to give offence, I rose to my feet and retreated. The Emu watched me go sadly, his impression implied that he had hoped of better things for me”.

Images of Dwarf Emu Dromaius baudinianus: Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes: exécuté par ordre de Sa Majesté l'empereur et roi, sur les corvettes le Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendent les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804; [Historique] publié par decret impérial, sous le ministère de M. de Champagny et rédigé par M. F. Péron. Paris: De l'Imprimerie impériale, M.DCCC. VII. [1807]-1816. Holding Institution: Boston Public Library (archive.org) Sponsored by: Boston Public Library.

Our deep gratitude to Jane and Frank and of course to our dear friend Miles.